“Have you ever asked yourself, what happens when you flush the toilet?

Where exactly does your wastewater go?”

I have, because I am an environmental engineer who specializes in wastewater treatment in Ethiopia and Nepal. Going to the toilet outside of the main tourist areas in these countries is not an easy task. People that are used to sneaking into the next Züri-WC (public toilet in Zürich) as soon as they feel the need, but who also work or travel in third world countries know what I am talking about. In poor areas of these countries, as well as in many other parts of this world, finding a decent place to take care of bodily needs can be a challenge.

For me, going to the toilet in a “developing” country is just part of the job.

Believe it, or not, I am passionate about sanitation systems. As an enthusiast, I specialize in sustainable solutions for developing countries; I love to check out others people’s toilets. I analyze the functionality and take a deep look into to hole to find out where “things” go. I also assess possible environmental and hygienic concerns that might arise from the infrastructure. Unfortunately, my lists of potential hazards are often quite long. Indeed, I would not want my daughter or my son to use many of the toilets I have visited in the course of my work.

The fact is that 4.5 billion people worldwide do not have access to safe sanitation and this fact leads to the death of 361,000 children under the age of five every year due to diarrhea (WHO; UNICEF 2017).

Even though toilets in poor developing urban areas sometimes exist, the collection and treatment of wastewater is often neglected. More than 90% of wastewater is discharged directly into the environment without proper treatment (UNW-DPC 2013).

Fact #1: Sanitation is crucial for the protection of the human health and the environment and for social and economic development.

Improved sanitation has a return on investment of about $5.5 U.S. dollars for every $1 U.S. dollar invested (Hutton and WHO 2012)

Most of the return is in the form of saved time, enhanced productivity, reduced healthcare costs, improved education, protected water resources, and increased tourism among others. The United Nations recognizes the critical role of sanitation for development in its Millennium Development Goals (MDG), as well as in its Sustainable Development Goals. Despite these efforts, the world has been falling short of the MDG for sanitation even though it has met the goal for safe drinking water well ahead of schedule.

Why is there such a discrepancy? First, it is much easier to acquire votes or to raise funding for drinking water projects, than for wastewater. Second, the focus of most sanitation projects in the past has been on toilets without taking into account requirements for collection, treatment, operation, and maintenance. This focus resulted in the selection of inappropriate technologies and a high rate of project failure.

A sustainable sanitation system requires six main criteria: it should safeguard (1) human health and (2) the environment, be (3) technically, (4) institutionally, and (5) socio-culturally appropriate, and (6) financially viable (SuSanA, 2008).

In Switzerland, it has taken many years and a lot of money to build the sanitation system infrastructure. It consists of several hundred thousand kilometers of pipelines, pumps, reservoirs, and treatment plants complemented by an institutional framework of skilled personnel that guarantee its sustainable operation and maintenance (Maurer, 2016). Such systems work here in Switzerland, because we have enough water, money, and technical knowledge. These are things that do not necessarily exist in expanding urban areas of developing countries. Today, sanitation experts agree that conventional sewer-based sanitation cannot be the solution for all of the world’s sanitation needs. Many (old and novel) alternative solutions including onsite, decentralized, and dry sanitation exist. Several of these solutions demonstrate opportunities for expanding urban areas in developing countries including: (i) reduced water, space, and energy requirements; (ii) increased opportunities for community participation in planning, construction, as well as, in operation and maintenance; (iii) increased private sector involvement for the collection and treatment of waste; and (iv) cost savings through resource recovery.

Fact #2: Engineers are developing a broad range of potentially sustainable sanitation systems, but there is not one solution that works for all circumstances.

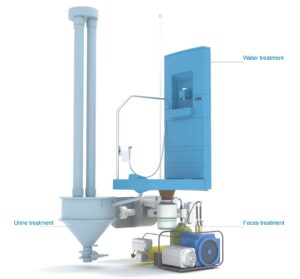

Two types of novel sanitation technologies:

The type of system used depends on site-specific conditions (e.g. population growth and density, climate, water and energy availability, and financial resources). Stakeholder preferences also influence the value or importance of the different sustainability criteria (mentioned above). For example, a lower treatment performance might be acceptable if the costs are lower or operation and maintenance is simpler.

Consequently, identifying a locally appropriate and potentially more sustainable sanitation system option can be a complex multi-criteria decision problem. Urban planners in developing countries are simply overwhelmed by this complexity.

Therefore, the selection of sanitation options are often randomly assembled showing a lack of transparency and a preference for conventional, but inappropriate approaches.

Fact #3: Tools and data are needed to support decision makers and urban planners in identifying locally appropriate sanitation options.

The selection of a locally appropriate sanitation system should: (i) Be systematic in order to be transparent; (ii) Consider entire sanitation systems (not only toilets); (iii) Be based on readily available data in expanding urban areas of developing countries; and (iv) It should look at conventional, as well as, novel technology options. In my work as a doctoral student, I have the opportunity to develop methods that fulfill these requirements. The methods are developed in collaboration with my partners in Nepal and Ethiopia. As a member of the ETH Zurich community, I have access to the state-of-the-art knowledge on a very broad range of both novel and conventional sanitation systems. This knowledge can be used to support sanitation planners in developing countries to find the right sanitation options for their particular situation.

The ultimate goal of my work is to improve access to sanitation in developing areas. I achieve this goal by providing the methods to identify more appropriate and eventually more sustainable sanitation solutions.

As a former consultant in development cooperation, I was motivated to pursue this PhD research by the problems I often encountered in my practice. This means that my research is designed to have a positive impact on the livelihoods of poor people in developing countries. It is a privilege to spend time and resources to in solving these problems. Professor Max Maurer from the Department of Urban Water Management at ETH Zurich and my co-advisor Dr. Christoph Lüthi from the Department of Sanitation, Water and Solid Waste for Development at Eawag, as well as the Sawiris Foundation for Social Development make this research possible.

Literature

Hutton, G. and WHO (2012) Global costs and benefits of drinking-water supply and sanitation interventions to reach the MDG target and universal coverage, World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, Siwtzerland. URL: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/global_costs/en/

UNW-DPC (2013) Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture. Liebe, J. and Ardakanian, R. (eds), UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development (UNW-DPC), Bonn, Germany. URL: https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:2661/proceedings-no-11_WEB.pdf

UNWater (2008) Sanitation is an investment with high economic returns, United nations interagency mechanism on all freshwater related issues including sanitation (UNWater), New York. URL: https://esa.un.org/iys/docs/IYS%20Advocacy%20kit%20ENGLISH/Fact%20sheet%202.pdf

Hutton, G., Haller, L. and Bartram, J. (2007) Global cost-benefit analysis of water supply and sanitation interventions. Journal of Water and Health 5(4), 481-502. URL: http://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/resources-and-publications/library/details/784

SuSanA (2008) Towards more sustainable sanitation solutions – SuSanA Vision document, Sustainable Sanitation alliance (SuSanA). URL: http://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/resources-and-publications/library/details/267

Maurer, Max (2016): Den Umgang mit Wasser neu gestalten https://www.ethz.ch/en/news-and-events/eth-news/news/2016/06/den-umgang-mit-wasser-neu-gestalten.html

By Dorothee Spuhler

Dorothee Spuhler is a doctoral researcher at the Chair of Urban Water Management, ETH Zurich and at Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology). Her doctoral project is partly funded through the Engineering for Development Programme, funded by the Sawiris Foundation for Social Development . Before starting her research, she has been working several years with planning and implementing sustainable sanitation and water management projects in Africa, Asia, South America and Switzerland. Read more about her project here.

Dorothee Spuhler is a doctoral researcher at the Chair of Urban Water Management, ETH Zurich and at Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology). Her doctoral project is partly funded through the Engineering for Development Programme, funded by the Sawiris Foundation for Social Development . Before starting her research, she has been working several years with planning and implementing sustainable sanitation and water management projects in Africa, Asia, South America and Switzerland. Read more about her project here.