The Ministry for the Future

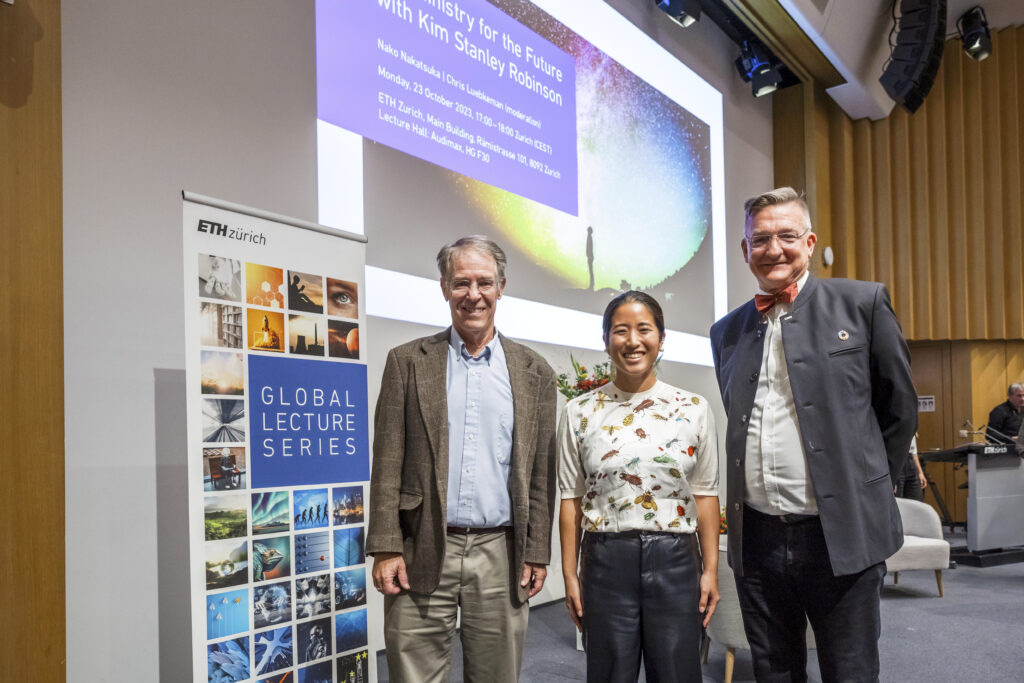

November 16, 2023ETH’s Head of the Strategic Foresight Hub, Chris Luebkeman, recently sat down for a Global Lecture Series talk with sci-fi writer Kim Stanley Robinson and Nako Nakatsuka, an ETH senior scientist in the Laboratory of Biosensors and Bioelectronics. Their focus: Robinson’s novel about climate change, and how to impactfully communicate highly complicated concepts to people from all walks of life.

And there is arguably no complicated concept more in need of being communicated right now, for all humans to understand, than climate change in general and global warming in particular.

Kim Stanley Robinson is best known for his utopian Mars Trilogy, which spans 200 years of Mars settlement and terraforming through the eyes of a wide range of characters. But it is his latest novel – The Ministry for the Future – that has grabbed attention, thanks to its call for urgent solutions to global warming.

So how did Robinson come to write this book, Chris Luebkeman asks, which he completed in just nine (!) months in 2019?

“I was under contract and a book was due.” Robinson smiles. But seriously, folks. At the time, people around Robinson talked about how humans can adapt to anything, even to climate change. Many argued there was no need to worry. “But two or three years before, I had run into this new bit of information: that human beings cannot live at wet bulb temperature 35.”

Studies had emerged with findings that “wet bulb temperature 35” – i.e. 35° Celsius at 100% humidity – is the threshold at which young, healthy humans can no longer adapt to the hyperthermia it creates within their bodies. The combination of heat and humidity at this level make it impossible for them to sweat, and their insides would essentially begin to cook. Wet bulb temperatures of 31 and 32 have already been known to kill the elderly and infants around the world.

Robinson felt compelled to spread this information in reaction to the climate change adaptation argument. “I thought this story had to be told, because it’s important, we have to keep global average temperatures down, (because) large portions of the earth (will) become inhabitable for certain times of the year in ways that would be fatal if you didn’t have air conditioning – and it’s exactly under conditions like these that the electrical grids go down, so you wouldn’t have air conditioning. You could be indoors, in the shade, without clothes on, with a fan on you – and still die within a few hours.”

The resulting book, The Ministry for the Future, is Robinson’s hopeful, optimistic near-future science fiction novel, packed with solutions that get Earth out of our impending dilemma. Published in 2020, it was recommended by US President Barack Obama and got Robinson onto discussion panels at events like the World Trade Organization, COP and the World Economic Forum. “It’s a better time (for this book) now,” Robinson says, “because people are aware.”

Nakatsuka says: “My family still lives in Tokyo, and my mom tells me it’s just too humid to live (there) in the summer now. They can’t leave their apartments … it’s happening now in Tokyo. It’s no longer something that is just a science-fiction novel.”

One of Robinson’s strengths in getting his point across is an approach to storytelling that expands perspectives for new ideas. He places the reader inside a wide variety of characters’ heads, so they can experience a multitude of aspects, a multitude of viewpoints, of the overall issue.

When he gets asked to participate in high-level talks off the success of his novel, “people invite me as if I could add something to the discussion. Very often I’m talking to a group of experts who know way more about the topic I’m speaking about than I do.” Robinson has found a way to share his language of storytelling with these experts, who he says are often “there to talk to a science fiction writer (as) a person from the future. So they can get out of their specialty and think about the totality. So they can imagine what could happen and what could come.” Robinson lets the scientists go inside the heads of their own characters to see what might happen. He allows scientists to become science fiction writers and in doing so, adds to the discussion in his own way.

Nako Nakatsuka sees this need for common language as well. She says, that as researchers, “we have to learn to be communicators. Storytelling is important to get research across better than dry tech. I’m a chemist by training, but I talk to engineers, neuroscientists, patients, clinicians, and we always speak a very different language. But we have to speak the same language to come up with solutions that actually work.”

In answer to the question whether technology will save us, Robinson asks: “What is a technology? Software is a technology and language is a software. Justice is a software, so justice becomes a technology. What are the crucial technologies? Language. Justice. Because then we can make (what we need). If everyone has enough… problem solved.”

Watch the full recording:

Find out more about our ETH Global Lecture Series here.