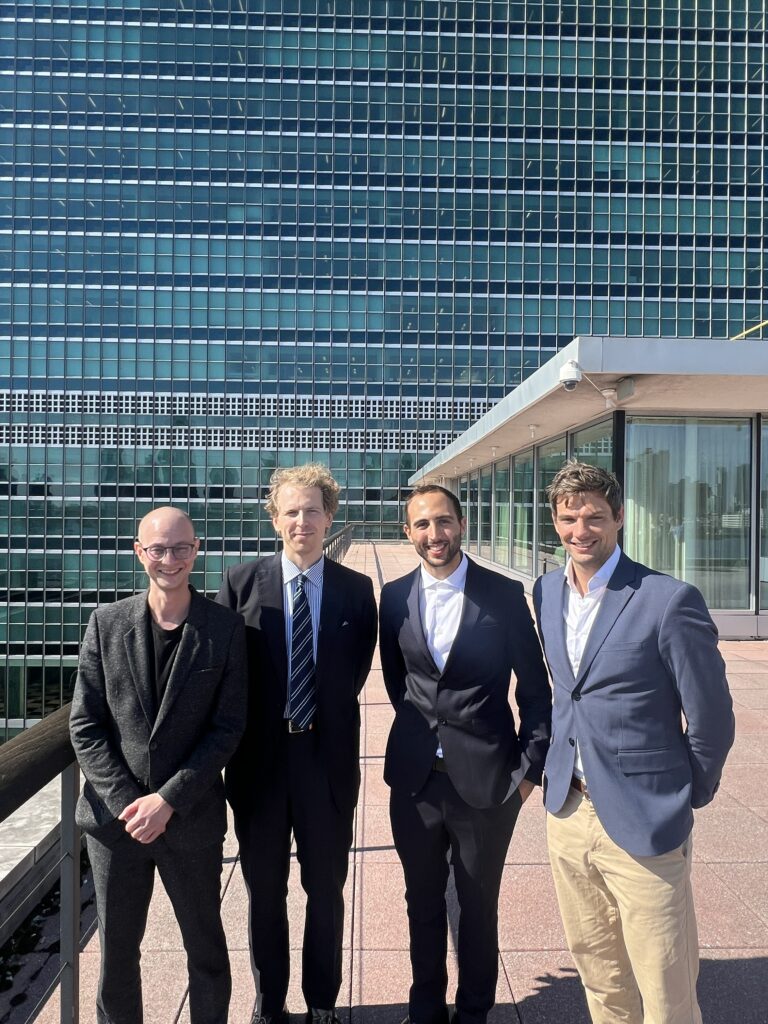

A Young Scientist at the United Nations

October 24, 2023When you start your Master’s thesis, there are a few things you can expect. Spending many days in a dim room with the blue light of your screen is one of them. What I hadn’t expected was that nine months later, instead of sitting in that dim room, I would be presenting key findings of my thesis in a bright office with glass walls overlooking the Hudson River on the 7th floor of one of New York’s most iconic buildings: the headquarters of the United Nations (UN).

My thesis supervisor, Sascha Langenbach, had been working on a joint research project between the Center of Security Studies (CSS) at ETH and the UN Operations and Crisis Centre since 2021. The project delved into conflict-event data gathered in UN peacekeeping missions and applied machine learning methods with the aim of mapping opportunities and challenges in building an event-prediction system for UN peacekeeping. My thesis and contribution to this project concerned a deep-learning prototype model that forecasts conflict-events within peacekeeping missions. And so, after managing to convince – or rather, beg – Sascha to bring me along, here I was, in New York, dressed in a fancy suit, ready to attend the meeting, stuck on the wrong side of the subway and racing to make it on time.

The meeting went very fast. We had to be clear and concise on the two main points we wanted to convey. First, we made clear that, no, we had not invented a crystal ball that predicted the next war. Second, we underscored the fact that we had laid the groundworks for a system using AI in conjunction with human intelligence. This human-in-the-loop approach resonated with UN officials and policymakers. AI is often perceived – not without fault – as a threat. For this reason, promoting a human-centred design is crucial when working with the public sector, as humans must retain oversight of the data gathering and analysis process as well as control over the decision-making process.

What I learnt is that it is crucial to reassure policymakers by showing them the benefits of a human-in-the-loop approach. This also helps scientists to view applied AI research not just as a modelling exercise, but as an iterative process that dynamically adapts with human feedback and experts’ domain expertise. As scientists, we often question the impact of our research, but this is difficult to assess. I believe that our awareness of the responsibility we bear, particularly when using powerful tools like AI, deepens when we confront real-world issues. It is therefore beneficial for personal development and how the tools we create are applied to engage with the relevant actors and understand their constraints and concerns.

This point lies at the heart of a broader partnership between ETH and the UN. Whilst we were presenting our project on the 7th floor, Joël Mesot and Guy Ryder, the Under-Secretary-General of the UN, signed a Memorandum of Understanding between the two organisations on the 10th floor. This partnership aims to encourage projects like ours and to promote technology-enabled social innovations within the UN. It also encourages scientists to engage more with the public sector in highly relevant areas like global peace and security, humanitarian aid, and the SDGs. So far, my experience has enriched me as a scientist who finds working on real-world issues stimulating and rewarding.