Building taste and value in the coffee sector: Strengthening the network between Brazil and Switzerland

May 8, 2024Brazil is typically a leading coffee producer. The region where I grew up produces around 25% of the world’s coffee. But it wasn’t until I left the place that I came to understand the impact (cultural, social, economic, environmental) of this activity on the planet, in the nation, and in my personal life.

Coffee has been traded as a commodity for centuries, and is responsible for shaping relations all around the world. The Coffee Paradox (Daviron and Ponte, 2005) is the name given to the phenomenon in which the price of coffee on the global market decreases, while the price of coffee available to the end consumer rises. The literature agrees that devaluation of coffee and its producers in the Global South and inflation in the Global North occurs mainly for two reasons. Firstly, higher value-added products are available in high income countries and secondly, services that exploit the intangible attributes associated with coffee have more profit. In this sense, specialty coffee blends from different parts of the world and the cool ambience of a cafe serving “direct to consumer” beans are really becoming a trend.

For the approximately 25 million people around the world who make a living from coffee (Fischer, 2017), most of whom are small producers, this inequality of income potential between production and end consumption is highly relevant. Although coffee growers infuse their products with their own cultural, subjective and immaterial attributes, they only get paid for the material aspects of their labour. These intangible qualities are overshadowed by the distribution channels, which now value subjective aspects that favour them. Producers’ immaterial qualities end up getting lost in the complexity of the value chains. What makes it possible for coffee sellers in the Global North to profit from the same intangible qualities that are considered irrelevant in coffee’s value when it comes to producers?

In search of answers, I went to Switzerland to investigate what the end consumer of specialty coffees is familiar with at the time of sale. In order to immerse myself in European consumer culture, during my stay I loved to spend my mornings studying at coffee shops, drinking specialty coffees from different parts of the world, trying to understand their unique, “valuable” qualities, as well as the ways they are marketed to the public.

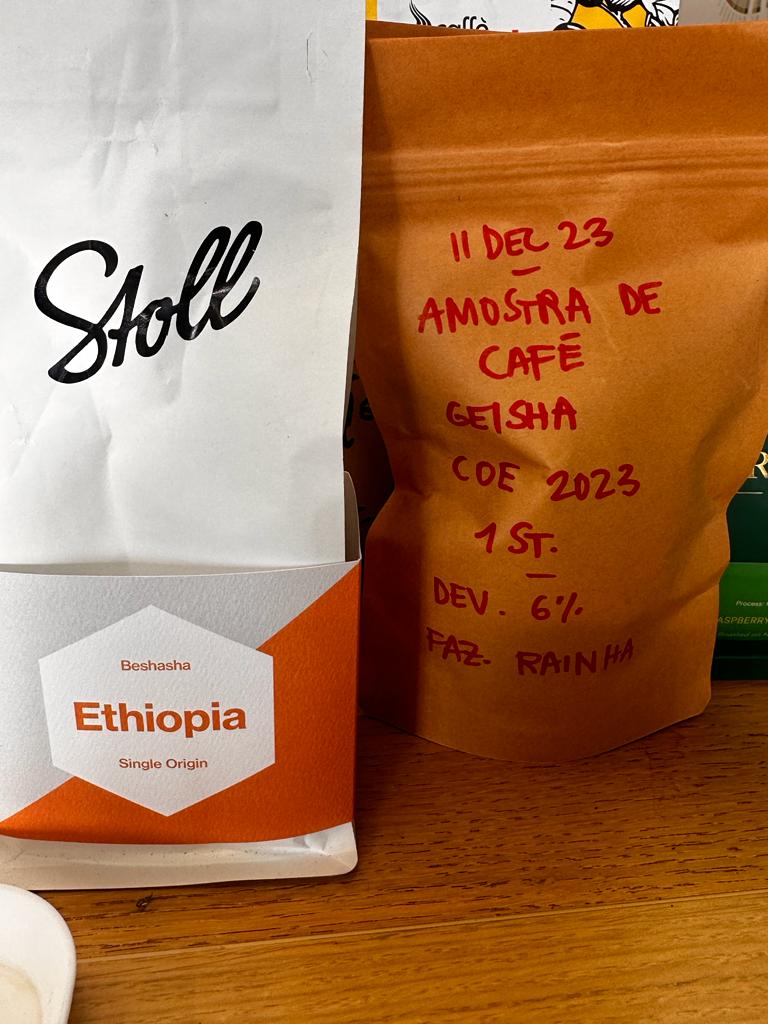

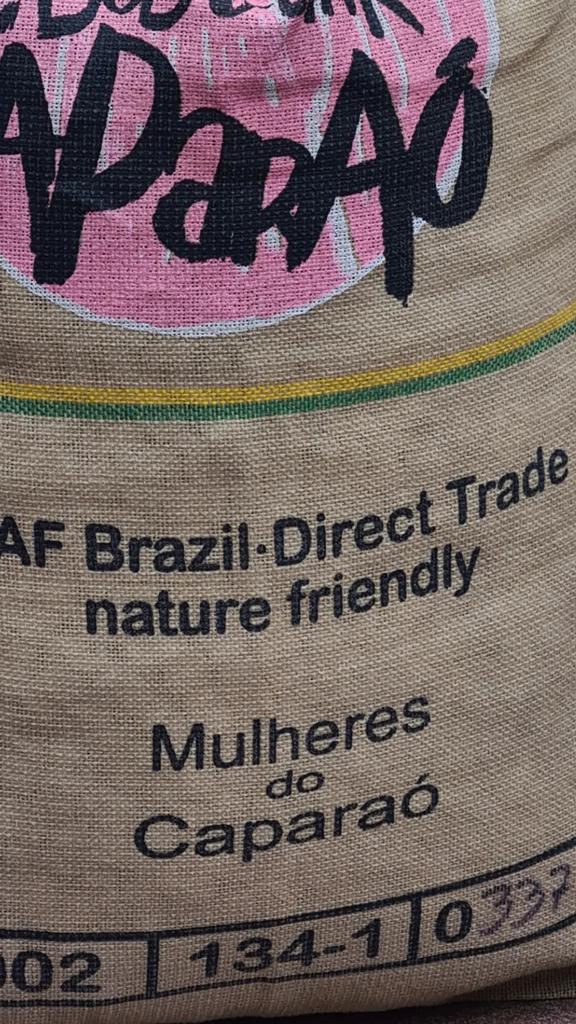

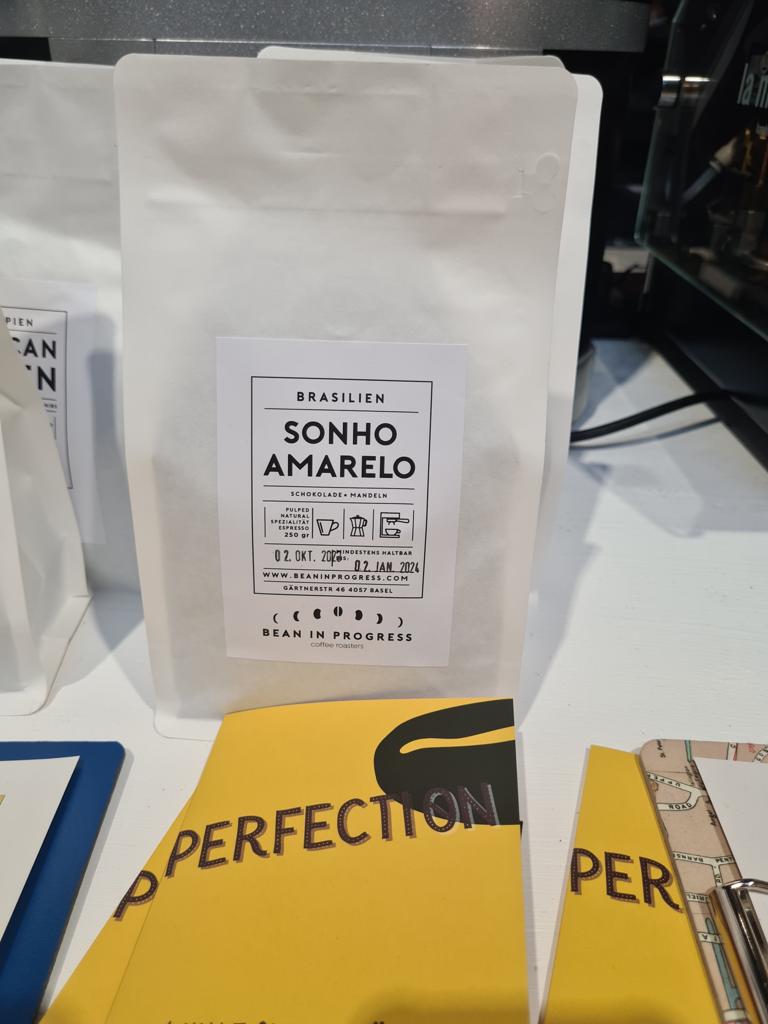

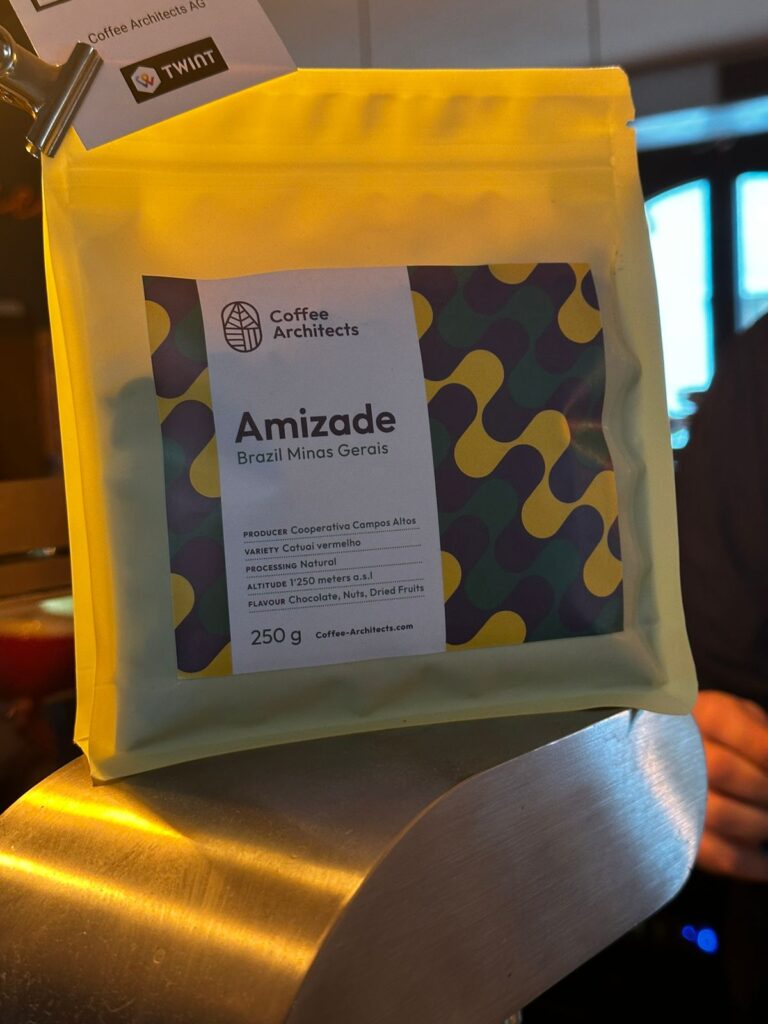

Although Brazil is the country that produces most of the coffee in the world, interestingly, it wasn’t as easy as I thought it would be to drink single origin Brazilian coffees in Zurich. I discovered that most coffees are sold in blends, mixing nationalities and sensorial profiles. However, I did find Brazilian bags at all the coffee roasters I visited. This observation helped me develop my hypothesis that the coffee transformers try hard to make the drinkable coffee unique, while at the same time having backups with similar characteristics, in case of climate extremes and other environmental or financial problems that lead to shortfall in acquisition of a certain coffee bean. In this sense, sellers in Zurich maintain the flexibility to substitute one producer’s coffee for another, thus undermining the producers’ market power. With this model, the control that producers have over the material means of production is no longer crucial to accumulation of capital. What matters more in this context is control over the channels of distribution and the means of symbolic production (Fischer, 2017).

The materiality of the Coffee Paradox is also observable in the number of coffee machines and different types of processing available for purchase in Swiss supermarkets, in stark contrast to the options common in Brazil. Although Brazil is the second largest consumer of coffee in the world, elaborate coffee machines are rarely found in private homes and are not sold in supermarkets.

At the same time that the Global South is undervalued in matters of production and distribution, it is also undervalued as an innovative protagonist in academia. Inequalities in the distribution and valuation of resources such as education, information and culture are the background of global power asymmetries, which consecutively impact individuals and their daily practices. At the Agroecology Europe Forum in Gyongyos, Hungary, one presentation highlighted the importance of Latin America, especially Brazil and its public policies, in promoting agroecology at the national level. But in contact with other colleagues, I discovered that I was the only Brazilian researcher present – and not for the lack of qualified, motivated and interested academics in my country.

Coffee is far from the only commodity subject to extreme inequality along the value chain. Our current food system is failing. It desperately needs diversity, inclusion, transformation and innovative practices. It is essential that non-hegemonic actors are recognized and take up spaces in this discussion. We are able to contribute to the debate with critical thinking and in matters of decoloniality and intersectionality. Learning can and should go both ways: the widespread success cases of social participation and social movements in support of agendas such as women farmers, agroecology, food safety, urban agriculture and environmental justice can inspire European practitioners and thinkers.

Many of these innovations from the Global South are technologies that can “add value” in agrifood products, like institutionalized participative certification, which decreases the costs of audit for smallholders as they get independent from third parties, or beans being valued according to the specific characteristics of the soil, climate and cultural know how of the land it is harvested, resulting in geographic indicators.

Whether through drinking a Brazilian coffee in Switzerland, producing articles in the lab or discussing Political Ecology in the classroom, my research confirms that the Global South is full of information, technologies and knowledge to be valued and appreciated, capable of reducing the asymmetries of power in the world. The journey doesn’t end here, as there is a lot of work ahead of us to shed light on the existing capacities of the Global South, in the coffee sector and beyond.

I would like to thank ETH4D for this empowering experience and thank Pr. Dr. Johanna Jacobi for the opportunity and all the support.