Hidden Conversations: The Stories from Field Research We Don’t Include in Publications

April 11, 2024“I could tell you what every tree is on this land, when it flowers and when it fruits. Our family has lived here for over a hundred years.

But we do not have a piece of paper saying this is our land.

The developers come in with their plan and all I can do is listen. Without a registration, it does not matter to the developers that I can name every tree, they still tell us that this is not our land. They are the ones with money, they can pay for it. I cannot.

So who will listen to us?”

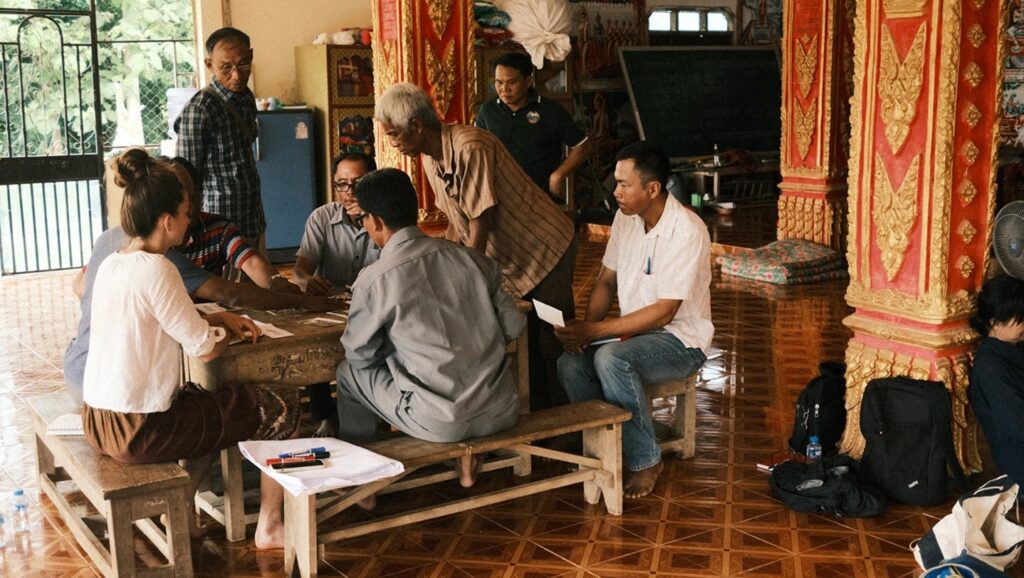

In the background of this voice recording is a rhythmic metallic pummelling. Torrents of rain. Recorded during the height of the rainy season in Southeast Asia, we are listening to remarks from a rural community in Laos. Together with another ETH master’s student, Jasmin Krähenbühl, and our translator, Khammeun, the three of us have been visiting remote villages in Laos to conduct focus groups for Jasmin’s and my master’s theses. Altogether, Jasmin and I will be in Laos for two months.

As part of an ETH4D pilot project, together with our research partners in Laos, we are investigating landscape change and the policymaking processes around it. We are here to gather data to be analysed and published in scientific publications. All our experiences, conversations, and findings will be distilled systematically and objectively into the “results” sections of these publications. This objectivity, though necessary for impartial scientific reporting, often also simultaneously hinders the expressiveness that makes these conversations so gripping.

The voice recording mentioned above came from our focus group conversations in the strikingly beautiful and highly touristic district of Vang Vieng. There had been a recent zoning proposal by foreign investors that, if approved, would convert the core 75 km2 into a “high-end adventure resort” (the area is roughly equivalent to the entire city of Zurich). This area would include 22 villages, one of which our interviewee belonged to.

Despite all 22 villages disagreeing with the proposal and each village writing to the Lao national government, they had received no replies, and continued seeing increasing numbers of foreign developers in the area. Villagers’ main concerns were not the development, but the lack of recognition of ownership and the resulting low compensation for their main (and often, only) source of food and security — their farming fields. At the same time, they were worried that their skills and education would not be enough for the jobs the foreign investors had promised to create.

These conflicts and stories were not directly reported in our master’s theses. Instead, for this specific conversation, in my thesis, I note how “residents reported that commercial development often encroached on their own lands, while having little means of providing feedback or opposition to these land use changes.” Clean and neutral, the process of systematic distillation expected from academic publications leads to writing that is objectively factual but remains sterile.

In these neutral tones, it is hard to convey the sense of urgency, desperation, and sliver of hope residents had when talking with us. They mentioned their hope that by talking with us – young, foreign researchers – we might help amplify their voices. It is hard to hear this and know that ultimately, we as young researchers, will leave, write reports and publications, and in these, we describe what we have seen in our “discussions” sections. The question comes back to: what are we doing for the people that live there?

The answer is that, hopefully, these publications contribute to a growing body of work regarding participatory policy-making, and the need to include and listen to local, often indigenous communities. From mounting research and pressure that eventually reaches the ears of policymakers and developers, policies could be drafted and implemented.

But policymaking processes take time. And in many places (Laos included), it is hard to say if this process for participatory decision-making will ever take place. So then what? More and more social movements are no longer waiting for government or corporate action, but rather insisting on change from the ground up. Time shared with these communities helped Jasmin and I understand many of their concerns. Perhaps in this way, our publications act as witness statements that build the evidence on which a demand for change can grow.

In the meantime, we stop the recordings, finish our publications, close our tabs, and eventually get acknowledged for the academic achievements we have garnered. But who has truly benefited? How can we bring the stories behind the research to the forefront? How can I look someone in the eye when they ask “who will listen to us?” and honestly reply “we will, and we hear you”?