by Alina Fiedrich, 19.09.2019

A Rocky Excursion to Canada

Field work – The excursion group (here with our guide Jean Goutier) poses on one of the rock exposures in front of the beautiful Canadian boreal forest. The most important tools for the geologist in the field include a rock hammer to take samples, compass, hand lens, and note book (photo credit: Dean Khan).

Canada’s wealth is based on a diversified economy, but a large part still stems from the exploitation and export of natural resources. Indeed, there is a whole range of ore deposits that enable the extraction of many different metals including gold, iron, copper, nickel, and zinc. As a student group of geologists with an eye on our future research and employment, we wanted to understand for ourselves how mining impacts academia and industry. What better way to learn than through an excursion to Canada?

Apocalyptic impact that generates wealth

When an asteroid or comet hit the Earth about 1.85 billion years ago, a large area of the Earth’s crust melted instantly. The rocks below and around the impact zone shattered forming a huge crater of up to 200 - 250 kilometers in diameter. The impact created two immiscible melts. Metals such as nickel, copper, and platinum accumulated in sulfide minerals near the base of the melt zone. On our excursion to Sudbury, Ontario, we first explored the geology of the impact structure in the field looking at rock exposures on the surface. Subsequently, Glencore, a large mining and trading company headquartered in Switzerland and with major presence in Canada, introduced us to their mining-related activities.

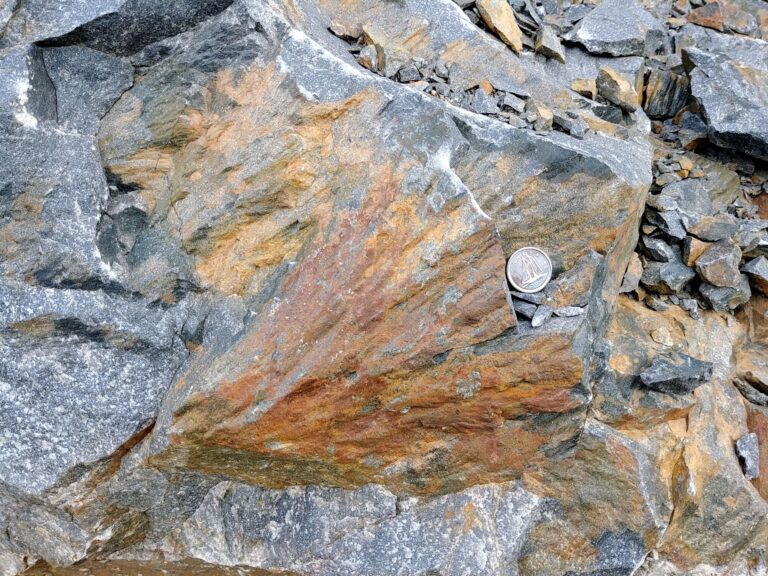

Working with super old rocks

The Archean is one of the Earth’s earlier geological periods in its 4.6-billion-year history. It was a time when oxygen began to accumulate in the atmosphere and the earliest forms of life first ap-peared on Earth. It was also a time when the Earth’s interior was a lot hotter than it is now and when the continents began to grow. The Abitibi Greenstone Belt formed during this period and hosts an incredible metal endowment, the origin of which is still a mystery. We had the opportunity to look at typical rocks and structural features of the Abitibi Greenstone Belt. In particular, we learned about the connection between major trans-crustal faults and gold mineralization. Several mining companies invited us into their mines and core shacks, so that we could take a look at rocks inaccessible on the surface.

Visiting the mines

By visiting various industrial facilities from mines to smelters, we learned about the whole process from finding and extracting ore to processing it into metals and remediating abandoned mining areas.

Mapping – Glencore’s exploration geologist Mike Sweeny is introducing us to the mapping area, where we learned how to make a detailed map that helps target a potential ore deposit (photo credit: Dina Klimentyeva)

Step 1: Finding an ore deposit

Major ore deposit discoveries are still made now and again in the northern reaches of Canada, based on geophysical exploration, mapping, and drilling. The Sudbury area, however, has been mined for such a long time that current developments mainly focus on expanding the existing works. Searching for ore near the existing mines is called brownfield exploration. It has an ad-vantage in that all the facilities for future mining activities are already present.

Drill core – This piece of ore-laden rock was recovered from close to 3 km depth below the surface. It contains nickel- and copper- bearing minerals that are of prime economic interest (photo credit: Kamil Bulcewicz)

Step 2: Mining the ore

Mining involves moving to deeper and deeper levels below the surface as ore bodies close to the surface become “mined out” and as technological advances allow for cost-efficient extraction at greater depths. Detailed mine plans are developed and constantly updated, while galleries are blasted and the rock material is extracted. Heavy equipment, some of which is remotely operated, and sturdy shafts are used to carry the rock material to the surface. Recording the lithologies and ore grades from underground rock exposures and drill core is essential to develop the mine in the right direction, and continuous monitoring of seismicity underground helps the miners stay safe.

Rock exposures in the Sudbury area generally have a black coating, the so-called “smelter crap”, which resulted from roast beds (large-scale fire pits to oxidize the ore minerals). Luckily, this primitive treatment is a thing of the past. Nowadays, the concentrated and milled ore is smelted in proper facilities. This photo was taken at the Sudbury smelter (photo credit: Farid Zabihian)

Step 3: Processing the ore

Large rotating cylinders crush the rock and mill it into fine grains that enable the separation of ore material from waste rock. Flotation plants process the powdered rock by separating desired min-erals with bubbles to which minerals attach as they ascend toward the top. A smelter oxidizes sul-fide minerals at high temperatures allowing for the extraction of the metals of interest. What sur-prised us was that Glencore has its own research lab (XPS) to control and improve the quality of the milling and smelting process. Both processes are sensitive to the input material (feed) and detailed microscopic and analytic work is required to understand why results differ from expecta-tions and how the process can be adjusted.

Step 4: Environmental remediation

Mining in the areas we visited started in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, and the early extraction and processing techniques were not exactly what we would call sustainable or eco-friendly. Nowadays, communities and mining companies alike are more environmentally conscious and keen on keeping their surroundings clean. This mindset resulted in the implementation of acid plants to prevent acidic rain, treatment of mining waste (“tailings”) so as not to harm the environment including underground back-fill of the rock where possible, and the remediation of old and “orphaned” mining areas.

Our impressions about working conditions in Canadian mines were positive overall. On the plus side, the very friendly Canadians, safe work environments, good salaries, and a large variety of potentially interesting jobs make Canada an attractive work place. On the other hand, under-ground work and the long working shifts divided our opinions. While this gives the employees several free days in a row, we wondered how families with children deal with this situation. In addition, it is dark, warm, and a bit noisy underground, so protective gear is required at all times. Some would say the working conditions are pleasantly stable, particularly with respect to the outside temperatures, ranging from +35 °C in summer to -40 °C in winter. The towns themselves are comparatively small but offer everything you need to live. In fact, many of the towns in remote areas only exist because of the mines. Consequently, quick weekend trips like the ones that are so common in Europe are not possible.

Underground mining - The Kidd Creek mine is the deepest base metal (i.e., copper-lead-zinc) mine in the world, outmatched in depth only by some gold mines, most of which are located in South Africa. The mine life is currently estimated to end in 2022, but exploration drilling from the deepest level (close to 3000 meters below the surface – the banner is a little outdated) is being performed in search of nearby ore bodies to extend the mine life. At such extreme depth, reliable ventilation and constant surveying of ground movements is of great importance (photo credit: Florian Viher).

Alina Fiedrich (photo credit: Michael Schirra)

About the author

Who is writing? I am Alina Fiedrich, a doctoral student at the Institute of Petrology and Geochemistry of ETH Zurich, and the main organizer of the Canada excursion (25 July – 9 August 2019). The excursion was run according to the principle, “by students – for students”, with the objective to learn about practical aspects of geology to find out where academia can contribute to society, and to motivate students into a career path in economic geology. It was organized in the framework of the society of economic geologists (SEG) student chapter of ETH Zurich, a student club. The excursion group was comprised of 15 students (bachelor’s and master’s degree-seeking, as well as doctoral researchers) mostly from ETH, with two guests from Poland and Serbia. We all have a strong interest in economic geology and a need for adventure in common. Previous trips went to Spain, Poland, Ireland, and Finland, so we felt the need to leave Europe and go overseas. For more information about the student chapter, please visit seg-students-ethz.webs.com or www.facebook.com/groups/segstudentchapterzurich/.

We would like to thank Charlotte Stone, Shirley Pélo-quin, Richard James, Ed van Hees, Pierre Bousquet, Jean Goutier, and Pierre Bedeaux for geological guidance, Dave Richardson, Brad Lazich, Mike Sweeny, Paul Wawrzonkowski, Sari Muinonen, Leigh Allen, Julie Coffin, Eric Archibald and colleagues, Yves Pré-vost, Roxanne Jacobs, David Pitre, Christian Tessier, and Émilie Gagnon for showing us around their work places, Scott Yarrow and Yvan Jost for organizing a fantastic excursion program, and Glencore, the Institute of Geochemistry and Petrology of ETH Zurich, and Pan American Silver for financial support.