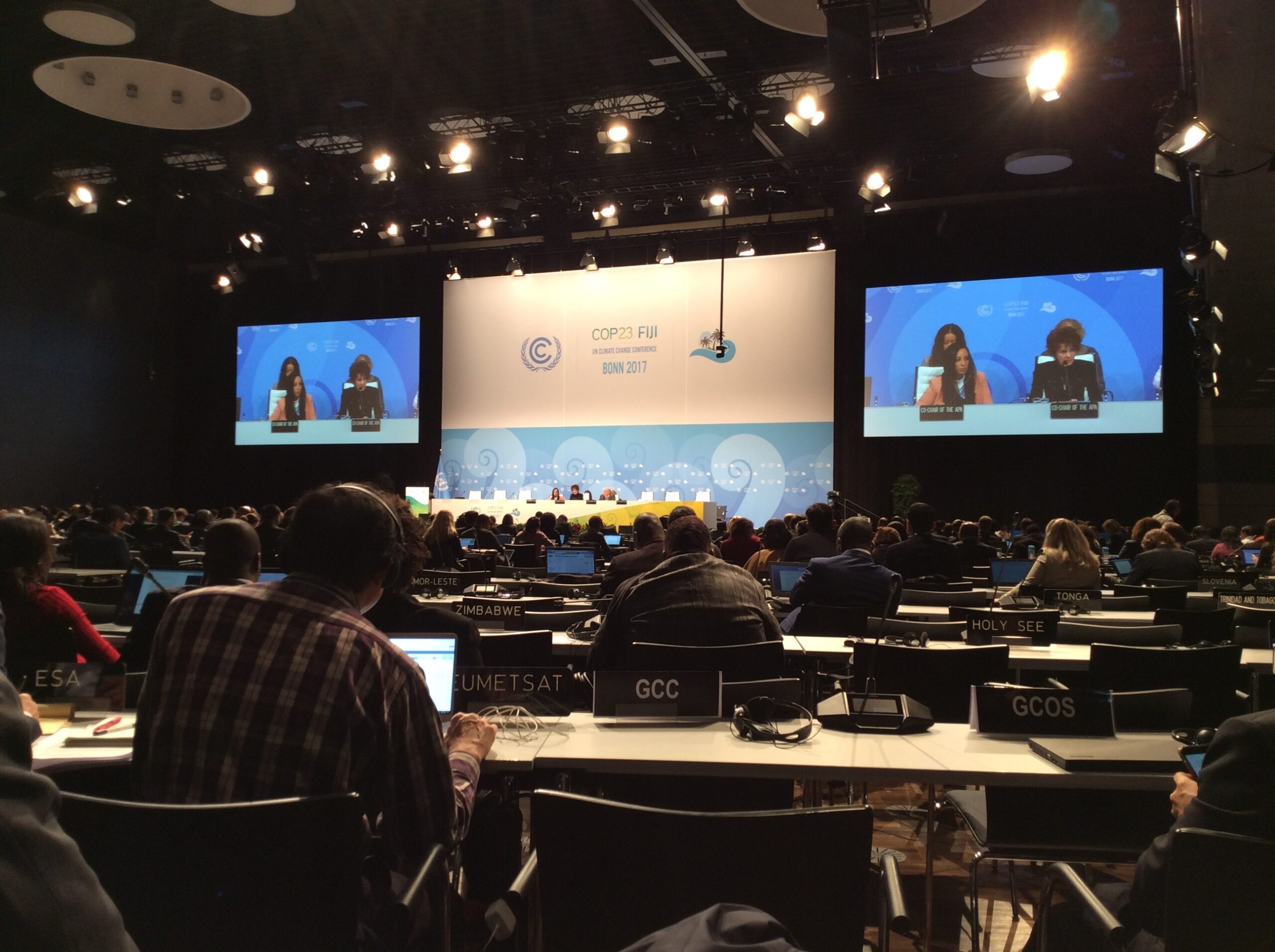

More than 25,000 party delegates, researchers and representatives of the civil society from 195 countries gathered together to talk about Climate Action at the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP23), that recently took place in Bonn, Germany. Three ETH Zurich students – Marie-Claire Graf, Anna Stünzi and Florian Egli participated in the COP23 and share their insights and impressions.

Marie-Claire: Advocating for the voice of the youth

A typical day at COP23 is intense – filled with negotiations, meetings, interviews, talks and presentations. Each morning starts with a YOUNGO meeting, the official youth constituency of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). I focused on one of the central negotiation topics, Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE – see Art. 12 of the Paris Agreement) that aims to educate, empower, and engage stakeholders – especially the youth. To enhance the implementation of ACE measurements, for example the promotion of education for sustainability at universities, YOUNGO organized meetings for national ACE focal points to exchange ideas on good practices and ways of implementing ACE activities in both a national and international context. Nevertheless, even as part of the youth constituency, I faced different obstacles. Some delegates didn’t take me seriously and sometimes I was not allowed to enter negotiations. In my opinion, the discussions should include the youth perspective much more than they do now, since the voice of younger generations is important for continued climate action.

Anna: Navigating between two zones and two mind-sets

The Bonn Zone offered a spectrum of activities, presentations and discussions, as well as, extra space for NGOs, scientists and civil society representatives. Along with other visitors, I learned about new energy-saving technologies, sustainable lifestyle patterns, and attended panels about global climate finance. By contrast, the discussions taking place in the Bula zone – the official space for delegation meetings – seemed to lose its participants in the technical details about procedural definitions and agenda-setting. Representatives from both sides attended my presentations – NGOs and civil society, but also party delegations showed a lot of interest in my research. In both, the Bonn and Bula zones there seemed to be common understanding that global ambitions are not yet sufficient. However, while I experienced an atmosphere of departure from the non-party participants, the formal negotiations seemed bogged down by party tactics, missing expertise, alliances and strategies. The discussion pace in the Bonn zone may be oblivious to the slow modus operandi of the Bula zone where 195 countries have to agree on the same wording. Nevertheless, in my opinion, the delegations could definitely have profited more with some drive from civil society.

Florian: An assessment of the COP-footprint

Aside from progress on the negotiations, how did the COP23 do in terms of its own emissions footprint? The UN announced, beforehand, their goal to achieve a climate-neutral conference environment. Although they sourced the food locally, there were few vegetarian options and these options were more expensive than other foods. Renewable energy heated, in part the conference tents; however, hidden outside the tents were the diesel generators supplying the remaining power. Although electric vehicles offered transport between venues, a large share of participants arrived by plane. The conference organizers encouraged the use of public transport (free for participants) and Deutsche Bahn (the German train system) timed their construction work between Bonn and Cologne to take place precisely during the two conference weeks. Closed railway stations in Cologne West and South created delays on regional lines. In the end, the conference’s carbon footprint seemed to mirror the actual negotiations – heading in the right direction, but at a low and slow speed.

New alliances and new partners to increase ambitions

So what did we take home from this experience? Rather than another milestone, the aim of COP23 was to prepare for COP24 scheduled later this year. This upcoming conference defines the parameters of the “Paris rule book” for effective implementation of the Agreement. While the slow progress should not shock us, reaching the 2° target demands much more in terms of discussion and action in subsequent years. In order to raise global ambitions, new coalitions have to be formed. In response to the withdrawal request from the United States. Switzerland could provide the strategic support they and other ambitious coalitions need.

The Swiss delegation does a great job in exchanging with a broad spectrum of civil society and business representatives. However, while external experts were part of the official delegation in former COPs, their representation has been reduced and especially academics were not included as official members of the party. Also, Switzerland could follow the example of Sweden and include permanent youth delegates in its delegation. In a recently published foraus policy brief, Anna and Florian suggest to negotiate not only among states, but also with sub-national government bodies, such as cities, and influential civil society actors. Additionally, Switzerland could leverage its extensive diplomatic network and skills to increase changes for an ambitious implementation of the Paris Agreement. A sensible step in that direction could be the offer to host a “milestone” COP26 in 2020 in Geneva. Past experiences, in Copenhagen and Paris, have shown that skilful preparation and guidance through the negotiation process can either enable or obstruct successful negotiations.

UNFCCC – the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is an international environmental treaty negotiated at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. It entered into force in 1994 and today it has near-universal membership. The 197 countries that have ratified the Convention are called Parties to the Convention.

The UNFCCC’s main goal is the stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interferences with the climate system.

A Conference of the Parties (COP) is the governing body of an international convention, thus a regular meeting of all members. The UNFCCC is a convention with an annual COP.

The Paris Agreement is an agreement within the UNFCCC, which was negotiated at the COP21 in Paris 2015, addressing climate change mitigation, adaptation and finance from 2020 onwards. The Agreement aims to keep the average increase of global temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius with respect to pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees only.

More information: http://unfccc.int/2860.php

About the authors

Marie-Claire Graf studies political and environmental sciences, and is active in Swiss Youth for Climate. She currently serves as President of the Swiss Association of Student Organizations for Sustainability and as Vice President of the Student Sustainability Commission at ETH Zürich.

Anna Stünzi is a doctoral candidate at the Center for Economic Research at ETH Zurich. She attended the COP23 and gave two presentations about the equitable distribution of the remaining carbon budget to achieve the 2° target, part of her scientific research[1]. Anna is Co-leader of the foraus programme, “Environment, Energy and Transportation”.

Florian Egli attended the COP23 in Bonn as an observer. He is a doctoral candidate at the Energy Politics Group at ETH Zurich, the Vice President of foraus and a co-author of the most recent foraus policy paper on ways forward for the Swiss climate policy.

[1] One event organised by the Swiss delegation (“soirée francophone”) and one event organised by an NGO (Energies 2050) in the Bonn zone.